The question of a tax on extreme wealth comes up now and again in the Irish news cycle but never seems to gain any significant traction. Why is that? One thing we notice is as soon as someone mentions wealth taxes, hoards of people are quick to reply saying Ireland already has a plethora of wealth taxes in the form of property taxes etc…

On top of that, it is not a vote winner. Most people have some form of wealth so it is understandable for the topic to be a bit triggering. But the majority of proposals to tax wealth are proposals to tackle extreme wealth specifically.

What is a wealth tax?

A wealth tax is a tax on an entity’s holdings of assets or an entity’s net worth. This includes the total value of personal assets, including cash, bank deposits, real estate, assets in insurance and pension plans, ownership of unincorporated businesses, financial securities, and personal trusts.

In short, it is an annual tax, payable on the total net value of your assets held.

In its report on the Irish Tax System for foreigners moving to Ireland, big 4 accounting firm Deloitte states unequivocally: There is no wealth tax in Ireland.

Not everyone agrees.

Former Taoiseach Leo Varadker has been quoted in the Irish Independent as saying:

“We already have wealth taxes in Ireland.” [1]

“Our income tax system is regarded to be one of the most progressive in the world. Fewer than 1pc of people in Ireland pay more than 20pc of income tax (total revenue).”

We find this statement around income tax to be largely correct at the time of writing. He continues:

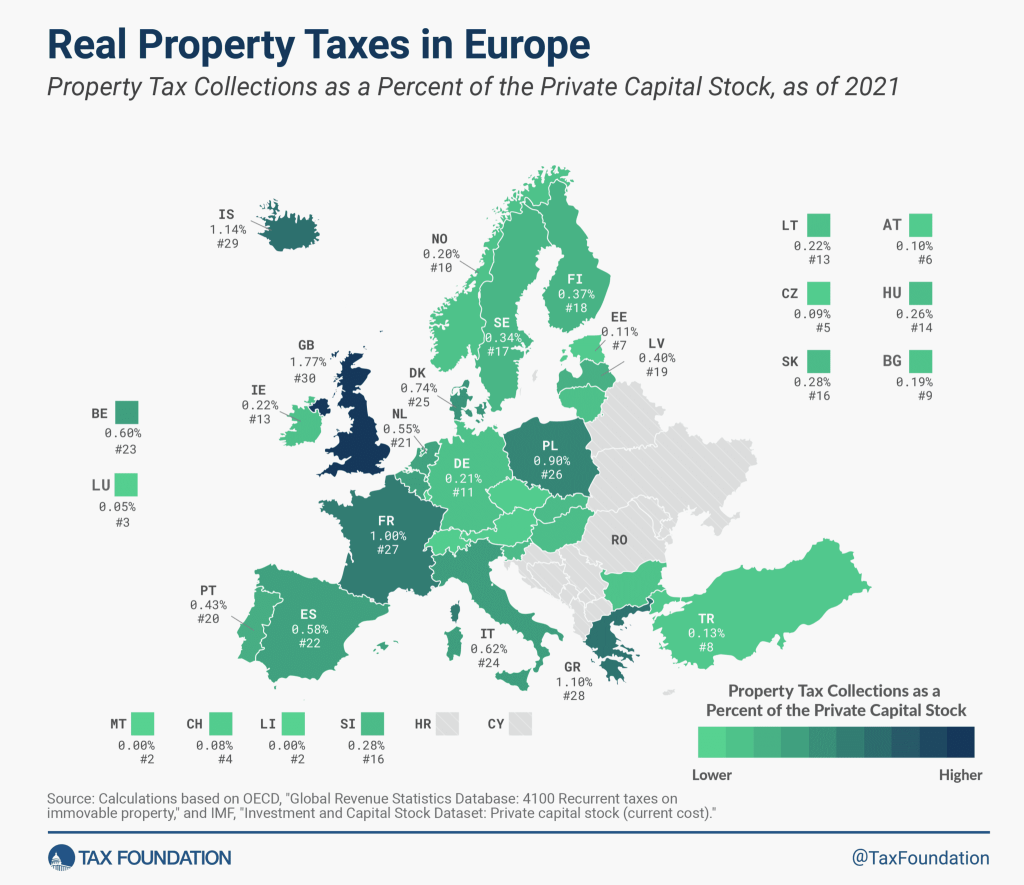

With the Local Property Tax, “the bigger and more valuable your property, the more property tax you pay. Those who have modest properties pay a modest amount. Those who have no property pay nothing at all.” This is factually correct but it is somewhat misleading. We know from multiple source on property taxation that property taxes in Ireland are relatively low by european standards.

He goes on to cite Capital Acquisitions Tax.

“That’s a tax on inheritance, for example, a tax on gifts. And Oxfam pointed out in their report that in two-thirds of countries there is no inheritance tax at all. In Ireland it is 33pc. We also have Capital Gains Tax, which is a wealth tax, and the rate there again is 33pc. The average across the world is only 18pc.

“So that gives you a good example of the kind of wealth taxes that already exist in our country.”

However, he leaves out the tax free allowances for inheritance such as 16,250-335,000 euro depending on your relationship to the disponer. A report generated by RTE also states that “Due to exemptions and tax-free allowances, few people pay Capital Acquisitions Tax” [13]

We found the figures quoted above to be factually correct and rates of tax and thresholds for capital acquisitions/gains can and should be debated. However, the assumption he draws from this that we have wealth taxes in Ireland is still incorrect. The taxes he has mentioned are largely event-based, one-off taxes and whilst they do serve the function of reducing wealth inequality (assuming they are paid), they do not meet the definition of a wealth tax.

Time to return to our definition of what is a wealth tax. This time from the spanish government tax website:

Wealth Tax is levied on the net wealth of individuals, i.e. all the assets and rights of economic content of which they are the owner, less any charges and encumbrances that reduce their value, as well as the debts and personal obligations for which the owner is liable.

The Government is committed to creating a fairer, more equal Ireland. While the calls for a specific wealth tax are understandable, there are already a number of wealth taxes in place including Capital Gains Tax, Capital Acquisitions Tax and Local Property Tax. Revenue estimates that these taxes raised over €2.8 billion last year.

Michael McGrath, former Minister for Finance [14]

The Irish Times reported on April 4th 2024 that Ireland’s billionaires saw their wealth grow by more than €15bn last year [2].

There are now a total of 11 Irish citizens on the exclusive list of billionaires, all men, including two new entrants who are both aged in their twenties. Their total net worth reached $52.9 billion (€49.12 billion) in 2024, a significant increase on $36.2 billion (€33.61 billion) last year.

The wealthiest Irish citizen, ranked 228th richest person in the world with a fortune of $9.9 billion or $9,900,000,000 having inherited a company in 2022 from his father.

In her example of wealth taxation, US Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren asks us to imagine two people here: an heir with €500 million in yachts, jewellery, and fine art, and a teacher with no inherited wealth or much savings in the bank. If both the heir and the teacher bring home €50,000 in labour income next year, they would pay the same amount in income taxes, despite their vastly different circumstances. Increasing income taxes won’t address this problem and as already mentioned Ireland has the second most progressive income tax system in the OECD (assuming we keep the top rate of USC, watch out for that [3]).

As explained by Thomas Piketty, a professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics, growing wealth concentration is in fact a natural tendency of capitalism. That’s why we need a tax on extreme wealth. Many have argued that it is necessary to protect the system from eventually threatening itself for extreme inequality is bad for democracy, particularly when a decent share of national wealth is no longer owned by a large middle class.

The findings of an Oxfam report into global inequality presents an opportunity for a renewed debate on the need for a wealth tax in Ireland, according to Social Democrats finance spokesperson who states:

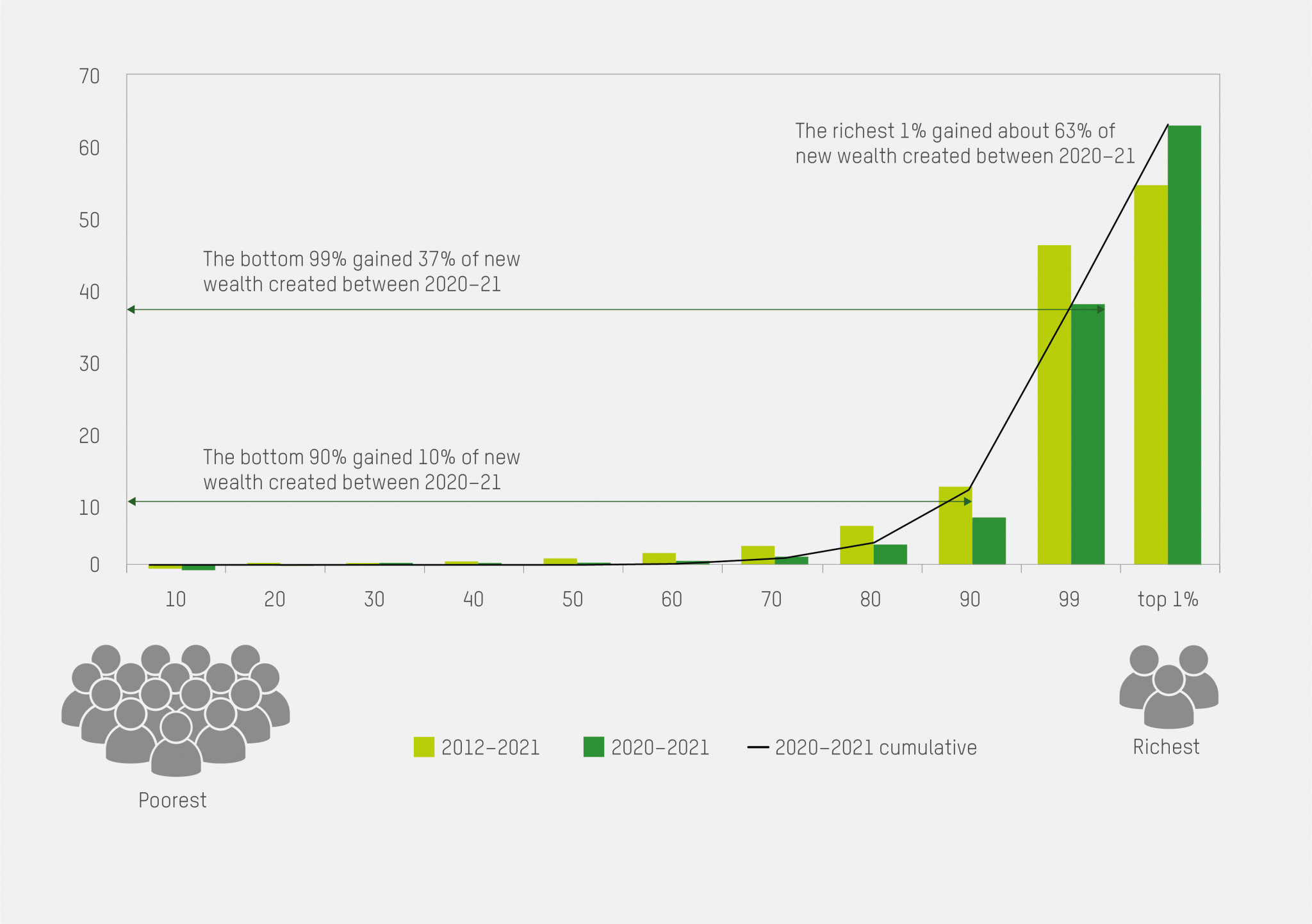

“Oxfam’s report, which has been released as political leaders gather at the World Economic Forum in Davos this week, makes for stark reading. It reveals that the richest 1 per cent in the country hold more than a third of Ireland’s financial wealth. In addition, it found that the country’s two richest Irish billionaires have more wealth than the bottom half of the population.”

Oxfam found that for every €93.15 of wealth created in the last ten years, €31.67 has gone to the richest 1pc and less than 50c to the bottom 50pc.

Why is this alarming and why is it only being reported by Oxfam and not circulated heavy by more mainstream Irish news providers?

There are a myriad of reasons why this could be the case but more importantly we should be discussing what the benefits of such a tax would be to our country. A wealth tax could raise significant funds to build more social and affordable aparment schemes lifting people out of poverty and promoting social cohesion. If one third of financial wealth in Ireland is owned by just one percent, then, almost by definition, that makes everybody else in Ireland poorer but particularly those who do not own their own accommodation.

It means that 66% of the wealth in Ireland has to be divided somehow between 99% of the population, reducing the net wealth of everyone else. But didn´t rich people generate their own wealth?

Yes and no. For example, a company that sets up in Ireland and becomes a billion dollar company, must make use of the infrastructure this country has, its education system, broadband, its roads, its security and healthcare, which are funded by the regular taxpayer. Having citizens who hold extreme amounts of wealth (north of 50 million euros for example) generates a problem for everyone else, because quite simply, that wealth is money that is no longer available to everyone else. More specifically, it hurts social mobility, the ability of individuals to move up the social ladder in a society.

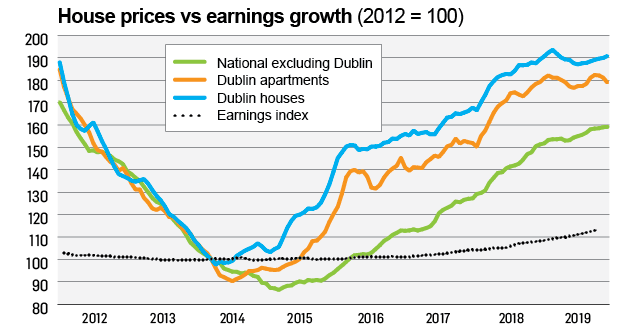

Can you get ahead by working hard? Luckily, to a certain degree, you can still move up the socio-economic ladder in Ireland. We are not nearly as far gone as our neighbours in the UK or USA with regard to overall wealth inequality and subsequent collapse in living standards. Still, as a young person you wjll notice that your capacity to climb the socio-economic ladder has vastly decreased since the generation of your parents and your grandparents. This is because the relative gain you make in terms of achieving a higher income will largely be erased by your costs of living, in particular rent, which is largely controlled by private industry and market capitalism in Ireland. The saying that millenials in Ireland will be the first generation to be poorer than their parents is very much still true today. In many cases, renters can expect to pay over 50% of their montly salary to keep a roof over their head. In order to escape this, you either have to continue to live with your parents (assuming this is an option), or emigrate. We know that people/companies (not all) with extreme wealth tend to reinvest their wealth by buying up property, often cash buyers with deeper pockets. This in turn leads to less opportunity for ordinary people to compete, adding another factor to the pie-chart of factors that have lead to and are sustaining irelands housing crisis.

This is wealth inequality at play. Aside from the property shortage on-hand, those who find themselves outside of home ownership are forced to make life decisions about their current and future relationship prospects based on their living situation. What sort of government decisions made this worse for people?

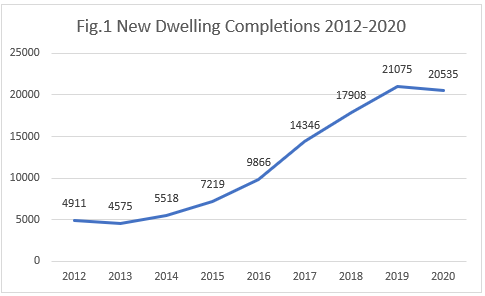

Aside from the obvious lack of social and affordable homes built during the period 2011-2018 in particular, the following decisions amongst others arguably exacerbated the problem:

Urban Regeneration and Housing Act 2015: This act, introduced under a Fine Gael majority coalition government introduced a specific planning designation for Build-to-Rent developments. This streamlined the planning process for these projects, potentially making them more attractive to developers.

Focus on Part V obligations: Prior to 2015, planning permissions for large developments often involved a requirement for the developer to set aside a portion of the land or units for social housing under Part V of the Planning Acts. The 2015 act tweaked Part V, allowing developers of Build-to-Rent projects more flexibility in how they fulfill this obligation. This could involve providing financial contributions instead of land or units.

It’s important to note that the concept of Build-to-Rent existed before these legal changes, but the 2015 act specifically addressed and potentially encouraged this type of development.

How would a wealth tax help this problem? If large-scale property owners were forced to pay a wealth tax upon reaching a certain net wealth threshold, the buying up and hoarding of property for overpriced rentals and fierce competition ordinary citizens face to buy housing would begin to subside. This of course would be in addition to an increased stamp duty on the bulk buying of homes by investment funds and large-scale landlords. The question is how to set it at a rate with conditions/exceptions that are effective in taxing these super-wealthy individuals without penalising both working and middle-class homeowners and small private landlords?

Where to set the rate?

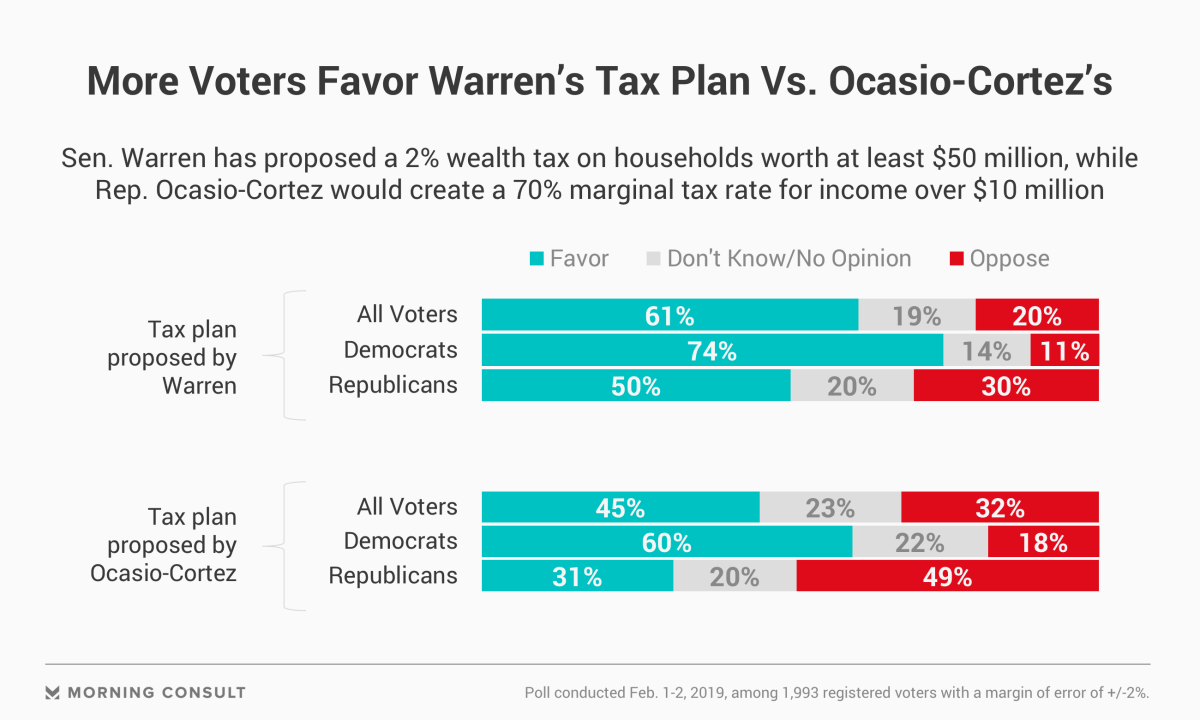

Coming back to our Harvard professor one interesting proposal came from Elizabeth Warren, the co-founder of the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, who proposed setting the entry rate in the US at 2% for net wealth over 50 million dollars. In effect this would mean the first 50 millions dollars of wealth will not see an extra cent in taxation, but on that 50 millionth and first dollar, you pay a 2 cent tax and 2 cents on every dollar after that. Unfortunately, despite this being a modest rate set at a very high threshold that would exempt the overwhelming majority of Americans, it did not see much action at a political level and was deemed a “radical”, “socialist” and “communist” idea by many pundits in mainstream media. But America has traditionally been a beacon of extrinsic capitalistic values and these concepts as per the previous examples have proven more palatable on european soil where wealth inequality is not so pronounced. Rates introduced in countries with existing wealth taxes often set the rate at between 0.3%-1.5% annually. It is worth remembering also that if at any point a persons net wealth falls below the threshold of say 10 milion euros, they would no longer have to pay the tax.

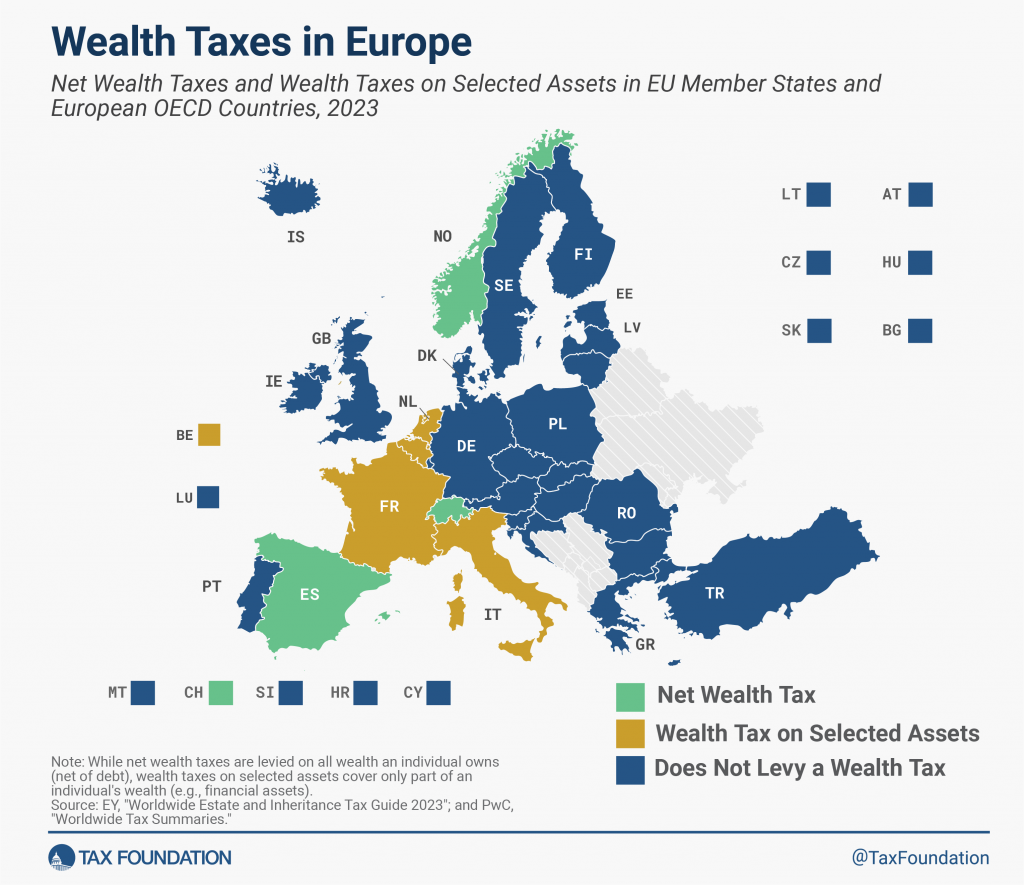

The OECD’s 2018 study of wealth taxes shows that the number of states which levied such taxes fell from 12 to just four between 1990 and 2017. Countries have abandoned wealth taxes due to concerns about their efficiency and administration costs, in comparison to the limited revenues generated. Some examples do persist however and countries such as Colombia introduced a new tax on net wealth in 2022[16].

Net Wealth Tax Examples:

Norway levies a net wealth tax of 0.95 percent on individuals’ wealth stocks exceeding NOK 1.7 million (EUR 140,000 or USD 160,000), with 0.7 percent going to municipalities and 0.25 percent to the central government. Norway’s net wealth tax dates to 1892. Additionally, for net wealth exceeding NOK 20 million (USD 1.87 million), the tax rate is 1.1 percent.

The tax is seen as a way to promote social equality, and social equality is seen as one of the most effective measures at tackling extremism.

Spain’s net wealth tax is a progressive tax ranging from 0.2 percent to 3.75 percent on wealth stocks above EUR 700,000 (USD 771,530; lower in some regions), with rates varying substantially across Spain’s autonomous regions (Madrid and Andalusia offer 100 percent relief). Spanish residents are subject to the tax on a worldwide basis while nonresidents pay the tax only on assets located in Spain.

Switzerland: Switzerland’s wealth tax is levied by individual cantons (states) and has significant variations in rates and allowances.

Wealth Tax on Selected Assets

France abolished its net wealth tax in 2018 and replaced it that year with a real estate wealth tax. French tax residents whose net worldwide real estate assets are valued at or above EUR 1.3 million (USD 1.43 million) are subject to the tax, as well as non-French tax residents whose net real estate assets located in France are valued at or above EUR 1.3 million. Depending on the net value of the real estate assets, the tax rate ranges as much as 1.5 percent.

Where is the discussion at in Ireland?

Looking at the manifestos of political parties in Ireland, it is no surprise that there are a spectrum of numbers on where to set the entry amount, with others opposed to wealth taxes completely.

Whilst not a party red-line, Ireland´s Green Party proposed in 2020 a wealth tax on individuals holding assets over €10 million[4]. Green Party Minister Joe O’Brien also pushed Government colleagues for a “one-off solidarity tax” on high earners and firms that were “highly profitable” during the pandemic.[18]. This was based off the International Monetary Funds call for such a one-off tax to be imposed.

On taxation, Ireland´s Social Democrats party is calling for the creation of a tax on “super wealth” that would be levied on assets. They set rates between 0.5%-1% and would also exempt assets like a family home with a value of up to €2m, as well as contents of the home[5]. The Social Democrats plan contains a level of detail we can´t discuss here, but its stipulations such as the exemption on the family home point to a wealth tax that has been carefully considered.

The Labour Party believes that targeted taxes on wealth must be recommended by the Commission. This will be crucial to ensure that we can renew the social contract and repair our society and economy when the pandemic passes and to enable us to make the necessary investments to deliver the kinds of public services the citizens of a rich, progressive Republic should be entitled to expect. [6] Labour notes and supports the prior work of NERI and TASC in examining the option for the implementation of a wealth tax in Ireland (McDonnell 2013).

Oxfam has called on the Irish Government to:

- Introduce a permanent wealth tax on net incomes over US$5 million. A flat rate of 1.5% could yield $4.5 billion (€4.2 billion), while a progressive rate on Irish multi-millionaires and billionaires at a rate of 2% on net wealth above US$5 million, 3% on net wealth over US$50 million, and 5% on wealth above US$1 billion could generate US$10.1 billion dollars each year (€9.2 billion.) Find our Methodology Note here.

- Close tax loopholes which could net €7.1 billion according to the Oireachtas Budget Oversight Committee 2022 report.

- Implement recommendations from the Commission on Taxation and Welfare which the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council estimated could yield €15 billion.

- Refuse taxpayers´ money to corporations who flout the law of the land or operate contrary to stated government policy.

On the global stage, they are calling for Ireland to be a voice for the Global South and support:

- Work by Thomas Picketty and Jayati Ghosh with staff from the UN, IMF and World Bank for clear targets on wealth inequality reduction

- A proposal by Joseph Stiglitz that every nation should aim for a situation where the bottom 40% of the population have around the same income as the richest 10% known as the Palma of 1.[7]

Note: The graph above shows an upper limit of 25,000 units for visibility purposes. However, it is important to note that in previous years Ireland built as many as 88,000 homes per year and the demand for annual builds currently sits far higher than 25,000 demonstrating the severe lack of housing completions in the preceding decade.

It helps to think of government wealth as a macro example of our own personal situation. If we own our own house for example, our largest living expense disappears, giving us more capacity to help those around us should we choose to. It is much the same for the western governments around the world who have lost much of their wealth in the previous decades. If governments do not own public assets such as hospitals and homes for the poorest, how can they compete with the super rich and help the poor? The only way to reclaim some of this lost wealth is through taxation of super wealth.

In the western world, as economies grow and the wealth of the richest swells ever bigger, living standards continue to fall. The great unfortunate irony of this, is for the working and middle classes this often results in a vote lean towards political parties that will lower taxes, when in fact the opposite is what is needed. Many voters are essentially shooting themselves in the foot here but it is a hard case to argue in the midst of such a collapse in public trust and it is likely that living standards will have to fall further and for an even larger portion of people in order for this reality to really hit home.

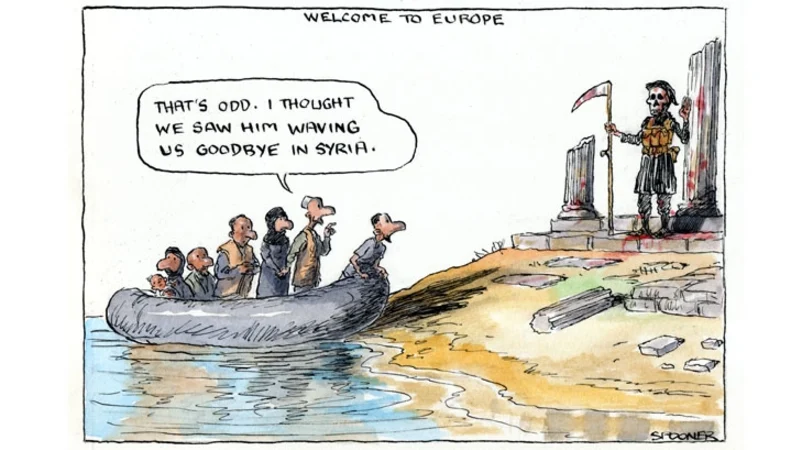

What do migrants have to do with this? Someone to blame for the western greed

Then we come to the poor migrants, threatened by a system that was rigged from the start. Net migration is up, although the population is still more than 2 million below what it was in pre-famine times. We have migrants working in our tech sector and in banking, but also in menial jobs in our hospitals, social services and kitchens. And bedsits and room shares for this latter group are increasingly common in a housing crisis that has been ongoing for well over a decade now. This type of sustained housing crisis does not discriminate amongst the working classes and whether they were born here or not.

When ordinary people start to feel a pinch, they may look to their news sources and politicians for answers. In some cases, they stumble upon politicians and media posts which try to pin the blame on our most vulnerable. Most people know that every immigration system has its flaws, needs constant review and proper implementation, there is no doubt about that. But are we potentially scapegoating the most vulnerable here to distract from the real threat of increasingly concentrated wealth in housing and supply/ownership? We see that in the period from 2011-2020 there was an approach to housing policy to see it as a wealth commodity moreso than a human necessity. Whilst some mild progress has been made, it is arguable that this ideology continues to this day. A far cry from the Dublin of 1966 where 50% of the entire population lived in what was then ‘Dublin Corporation’ housing [17].

Now a perfect storm of a lack of home builds plus favourable tax treatment to property funds is beginning to erode trust in establishment politics here in Ireland. But what perhaps has been most shocking of all is to now see a small number of those same established political figures leaning into this wedge issue of migration for political gain and more importantly, someone else to blame…

Alesina, Mino and Stantcheva (2018) show that for example right-wing respondents without a college education (a key demographic target for would-be populist voters) in multiple developed countries are significantly likelier than other citizens to believe that immigrants are unemployed and uneducated. By implication, immigrants are perceived to be both a source of blue-collar labor market competition and a drain on public coffers. A sense of betrayal results- distant elites support foreign “others” instead and at the expense of the “true people”.

Will a tax on extreme net wealth be a panacea for the rise of the far-right in Ireland or raise the funds to solve our enduring housing crisis or decrease the competition towards home ownership? It is very unlikely. It is just one of a handful of measures that could help improve social mobility in Ireland which is highly tied to housing. And the OECD´s study into wealth taxation notes it will be a challenge for politicians to convince the public that higher taxes on wealth and property are sensible. As stated at the beginning of this article, wealth taxes are generally not a vote winner. But that doesn´t mean we can´t start the conversation.

If you would like to donate to Médecins Sans Frontières: Mediterranean search and rescue please click here. Thank you.